[ad_1]

It’s not just something one can bury in the recesses of history because even today many cultures across the world accuse women of practicing black magic and witchcraft. And women accused of this proofless crime are still subjected to extra-judicial forms of justice, including mob vengeance and death. One of the most famous witch-hunt trials, the 17th-century Salem Witch trial in Massachusetts, has finally been “concluded.” The last Salem witch was officially exonerated by the state 329 years after she was accused of worshipping Satan!

The Last Salem Witch Is Probably Not the Last Witch Ever

The campaign to exonerate the last Salem witch, described as “a great way to do civics education,” was spearheaded by Massachusetts eighth-grade teacher Carrie LaPierre. Over three long and exhausting years, she fought to clear the name of Elizabeth Johnson, who had been branded along with 29 others for the crime of being a witch and a worshipper of Satan . While the rest of the accused had had their names cleared, Johnson’s name was never cleared of the charges.

A recent Massachusetts bill, which was passed due to the rare cooperation between a Democrat senator and a Republican governor, has cleared Elizabeth Johnson of any wrongdoing, making her the last Salem witch to be pardoned. The bill was tucked inside a 53-billion-dollar (44-billion-GBP) state budget signed by Governor Charlie Baker, reports The New York Times .

Elizabeth Johnson admitted to practicing witchcraft in the infamous 1692 trial. The 22-year-old was almost sentenced to death but, in the end, was allowed to live. She passed away in 1747 at the age of 77.

“I’m excited and relieved,” Carrie LaPierre, the teacher at North Andover Middle School, said in an interview on Saturday, “but also disappointed I didn’t get to talk to the kids about it,” as they are on summer vacation. “It’s been such a huge project. We called her E. J. J., all the kids and I. She just became one of our world, in a sense.”

LaPierre, a civics teacher, along with her students, campaigned vociferously to clear Johnson’s name. They were fortunately aided by a sympathetic senator, Diana DiZoglio, who was inspired by the meticulous work done by the 13 and 14-year-olds. The students had been inspired by the public school’s year curriculum on the notorious witch hunt , reports The Daily Mail .

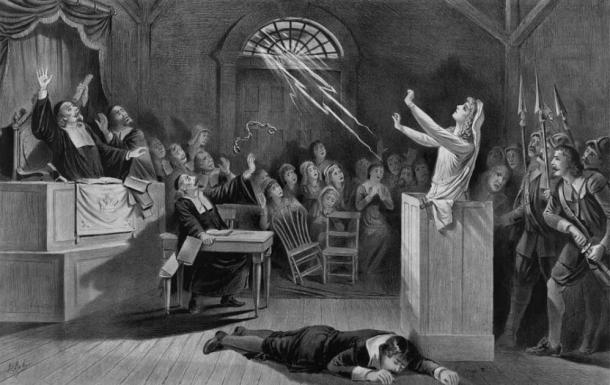

The last Salem witch, Elizabeth Johnson, who was pardoned by the state of Massachusetts in mid-2022, would have been tried in a courtroom like this one drawn by Joseph E. Baker. (Baker, Joseph E. / Public domain )

Justice for the Last Salem Witch – Who Wasn’t One At All!

During their classes, LaPierre came to the realization that whilst a horde of other accused men and women had had their names cleared, Elizabeth Johnson had not been accorded the same dignity. LaPierre met with lots of resistance from students who were indifferent to someone who had already died, and a lot of parents felt the same. LaPierre’s interest and motivation was further cemented by the work of a historian, Rhode Island archivist Richard Hite, who had penned a book on the matter.

Incidentally, LaPierre overheard the historian in conversation with another teacher, inspiring her to take on the pardoning process for the last Salem witch not pardoned. As per the peculiarities of the modern legal system , Hite could not have filed the case as he was from another state, making his potential appeal legally void. He graciously decided to share his work with LaPierre and allow her to take up the appeal. Hite, the author of In the Shadow of Salem , described people in the 17th century as a lot less sensitive on the whole.

“I certainly didn’t start this project,” LaPierre told makers of a documentary about her and her students’ struggles to exonerate Johnson, titled The Last Witch .

“The author, Richard Hite, who wrote the book about Elizabeth Johnson and discovered she had never been exonerated. He was a member at the Historical Society in North Andover, and it just so happened another middle school teacher was there, and they were speaking about this. And Richard is from Rhode Island , so he couldn’t’ do legislation. So, it was offered up to me, and I said, ‘sure, we’ll take it.’”

Johnson suffered from severe developmental disabilities and mental illness but was nonetheless sentenced to death for apparent collusion with The Prince of Darkness or Satan. Witchcraft was not as common a practice in the New World, compared to Europe, and the rate of conviction in Europe was much higher.

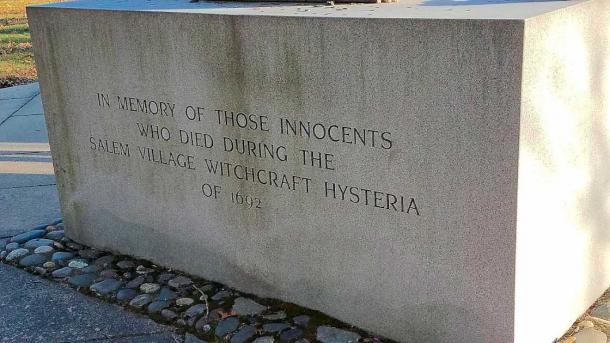

A memorial to the victims of the Salem witch trials in Danvers, Massachusetts, marking the 300th anniversary of the trials in 1992. (Francis Helminski / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Salem and Witchcraft: An Uncomfortable Exercise in Puritanism

There have been only 36 recorded witch executions in all of the Americas, compared to 12,500 in Europe. This is the reason that Salem achieved infamy in the United States, despite its much lower rate of conviction. Salem’s place in the popular imagination was aided and cemented by almost countless and endless references in cinema, film, literature, and television over the years.

In 1957, the Massachusetts Legislature passed bills to exonerate those who had fallen prey to the hysteria of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, only to exclude Johnson yet again. Johnson, with no descendants, no children, had applied for exoneration in 1712, only to have her plea rejected, even though Puritanical witch hysteria had died down by this point.

According to contemporary historians, the reasons an innocent person might confess to witchcraft were multiple. One was to avoid torture. Another was their belief in the accusations from family members and a Puritanical society dominated by highly-religious ministers. There was also a lack of trust in oneself and the confusion of separating bad thoughts or strange beliefs from what a real witch really was. The rule of numbers was also a factor. Those who didn’t confess were more likely to be tried and executed, compared to those who confessed.

Irrespective of the reasons, the prevailing mood is one of cheer for having cleared Elizabeth Johnson’s name of witchcraft finally and forever.

Top image: Examination of a Witch (1853) by T. H. Matteson, inspired by the Salem trials, which have been finally “closed” by the exoneration of the last Salem witch, Elizabeth Johnson. Source: Peabody Essex Museum / Public domain

By Sahir Pandey

[ad_2]

Source link