[ad_1]

Ancient burial sites in Egypt have yielded tattooed mummies, that are predominantly female rather than male. Over time, various debates have arisen about who these mummies were, in terms of their social status, and while that debate continues in the background, a new tattoo discovery has shed further light on the kind of tattoos found on female mummies. At the New Kingdom site of Deir el-Medina (1550 BC to 1070 BC), tattoo designs found on both mummies and clay figurines are likely connected with the ancient Egyptian god Bes , who protected women and children during childbirth.

The Tramp Stamp? Examining Who Was Tattooed

Publishing their finds last month in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology , researchers Anne Austin and Marie-Lys Arnette gleaned their evidence from two tombs they’d worked on in 2019. They also studied again clay figurines found at Deir el-Medina decades ago, which Lys Arnette, an Egyptologist, found were on the thighs and lower back area. These two depict Bes, and importantly tell us that the definition of the ‘tramp stamp’ is something overblown in popular culture.

A tattoo on the lower torso of a mummified Egyptian woman. ( Anne Austin /University of Missouri-St. Louis )

Analyzing the Two Mummy Tattoos

The first tattoo is from the human remains of a singular tomb explored in 2019 , which contained the hip of a middle-aged woman. On this hip, the portions of preserved skin show patterns of dark black coloration that would have probably run along her lower back. To the left of a tattoo is the image of Bes with a bowl – a symbol of post-natal ritual purity.

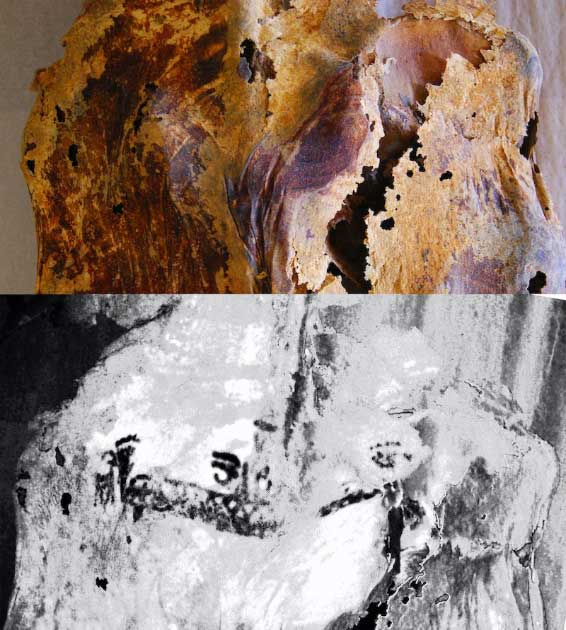

The second tattoo is also located on the body of a woman from a nearby tomb – a wedjat or Eye of Horus , with a possible image of Bes wearing a feathered crown. This was gleaned using infrared photography as the tattoo was really difficult to notice with the naked eye. This tattoo was related to protection and healing, and the depiction of a zigzag line was perhaps indicative of cooling waters that helped alleviate pain from menstruation and childbirth. As mentioned earlier, even the three clay figurines are decorated with tattoos along the thighs and lower back region, also depicting Bes.

“When placed in context with New Kingdom artifacts and texts, these tattoos and representations of tattoos would have visually connected with imagery referencing women as sexual partners, pregnant, midwives, and mothers participating in the post-partum rituals used for protection of the mother and child,” conclude the researchers.

Reconstruction of a tattoo on the torso of one of the mummified Egyptian women. ( Anne Austin /University of Missouri-St. Louis )

Females Dominated Tattooing in Egypt

“It can be rare and difficult to find evidence for tattoos because you need to find preserved and exposed skin,” study lead author Anne Austin, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, told Live Science . “Since we would never unwrap mummified people, our only chances of finding tattoos are when looters have left skin exposed and it is still present for us to see millennia after a person died.”

Moreover, tattooing has been seen to be an almost exclusively female practice in ancient Egypt. Mummies found with tattoos have most often been dismissed by male excavators who assumed the women were of a ‘dubious status’, describing them as dancing or chorus girls.

However, there is no evidence to suggest that tattoos in ancient Egypt specifically marked dancers, prostitutes, concubines, or individuals of a lower class. In fact, some of the mummies with tattoos were high status priestesses like Amunet . Early archaeologists often stubbornly clung to these derogatory labels and assumptions about those who got tattooed, trying to thereby deny their status and importance, even in a historical sense.

Examining Deir-el Medina: Site of Common People’s Lives

Deir-el Medina, an ancient Egyptian workmen’s village, lies on the western bank of the Nile , adjacent to the archaeological site of Luxor. The site was excavated in the early 1920s by a French team, contemporaneous to Howard Carter and his team’s discovery of Tutankhamun, and was known as Set-Ma’at or Place of Truth in the New Kingdom days.

It was planned urban architecture, with rectangular gridded streets and housing for the workers and artisans at the necropolis, who would leave days at a time to work on the tombs. They were called ‘Servants in the Place of Truth’, and while not enough is known about their lives, the site itself is unparalleled when it comes to the documentation of community life here.

At the heart of this site lies the so-called Great Pit – an ancient dump of pay stubs, receipts and letters on papyrus. These are the most reputable representations of the lives of common people, from almost anywhere in ancient Egypt. Yet, an important point of observation is that none of this correspondence mentions the practice of tattooing anywhere.

Top image: Tattoo on the left femur of a mummified Egyptian woman buried at Deir el-Medina. Source: Anne Austin /University of Missouri-St. Louis

By Sahir Pandey

[ad_2]

Source link